In times of impeding crisis, it’s worth reaching for the experiences from attempts at survival in situations of total crisis which don’t go that far back. One such great challenge for the nations of former Yugoslavia were the wars started after Yugoslavia’s breakup. The civil war which took place between 1991–1995 was the most bloody conflict in Europe since World War II. During this time, the part of former Yugoslavia that suffered the most was Bosnia and Hercegovina, an ethnically and religiously diverse republic located between Croatia and Serbia. One of the stages of this war was the siege of Sarajevo, which lasted 1430 days, from April 5th to February 29th 1996, and was led by the forces of the Serbian Republic and the Yugoslav People’s Army from the capital of Bosnia and Hercegovina against the majority, who wanted Bosnia and Herzegovina to be independent.

For the greater part of this siege, there was no electricity in the city, and people managed to sustain themselves thanks to the gardens surrounding their houses, green spaces in the city, and aid dropped by the army. In mid-1993 a 800 metre tunnel opened underneath the airport. It was the only route connecting the city under siege with the free part of the country inhabited by Bosnians. It allowed for them to transfer weapons and food.

One of the great figures of this siege was prof. Sulejman Redžić (1953-2014), a botanist who created shows on his radio station on how to enrich one’s diet by picking plants in the city, and then wrote a work that documented human nutrition during the siege. Sadly, this researcher was found dead in a forest near Sarajevo at the peak of his scientific career. The circumstances of his death are uncertain and may even point to political motives.

I first encountered Sulejman when reviewing his article. He then invited me to lecture as a guest at a plenary session of a conference he was organising. Spending time in Sarajevo, I heard many stories on how people coped with nutrition, both from Sulejman and his assistants as well as other Bosnians I had the chance to meet.

Life was really difficult. There was a shortage of everything. People ate whatever they could make out of airdropped pasta or powdered milk, they searched for nettles, and most of the space in gardens was taken up by vegetable patches. The first winter was the worst. There were even shortages of water and people hid from artillery fire in empty, unheated flats. Many people lost 20-30 kg of their body mass.

After surviving the first year and digging the tunnel, people started to cope better.

Here’s a link to an article on the use of wild plants for survival in Sarajevo:

Redžić, S., 2010. Use of wild and semi-wild edible plants in nutrition and survival of people in 1430 days of siege of Sarajevo during the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina (1992–1995). Collegium Antropologicum, 34(2), pp.551-570.

https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/85765

He later also wrote an article on the use of mushrooms and lichens in a different region of Bosnia and Hercegovina:

Redzic, S., Barudanovic, S. and Pilipovic, S., 2010. Wild mushrooms and lichens used as human food for survival in war conditions; Podrinje-Zepa Region (Bosnia and Herzegovina, W. Balkan). Human Ecology Review, pp.175-187.

Young leaves and stems were the most often eaten parts of plants. The most frequently eaten plants were: nettles (Urtica dioica), dandelions (Taraxacum officinale), coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara), common chicory (Cichorium intybus) and the common mallow (Malva sylvestris). Other often eaten species included the amaranth (Amaranths retroflexus), the common houseleek (Sempervivum tectorum), sorrel (Rumex patientia and R. acetosa), the common primrose (Primula vulgaris) and parsnip (Pastinaca sativa) roots. Other than that, they used the white clover (Trifolium repens), chickweed (Stellaria media), charlock mustard (Sinapis arvensis), wild radish (Raphanus raphanistrum), spotted dead-nettle (Lamium maculatum) as well as the bulbs of the Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus).

I was very moved by the conference in Sarajevo and my meetings with its inhabitants. I fell in love with the Balkans. Thanks to one conversation in the pub in the evening after lectures, with, among others, some researchers from Croatia, I started studying wild vegetables sold on the Dalmatian coast the following year. Since then I’ve gone to do research in The Balkans a few times a year, which, in the past few years, has been possible thanks to my NCN grant no. 2015/19/B/HS3/00471 entitled Traditional collection of wild edible plants on the islands of Dalmatia. Maybe now thanks to the quarantine in Europe I will find more time to write about this on my blog…

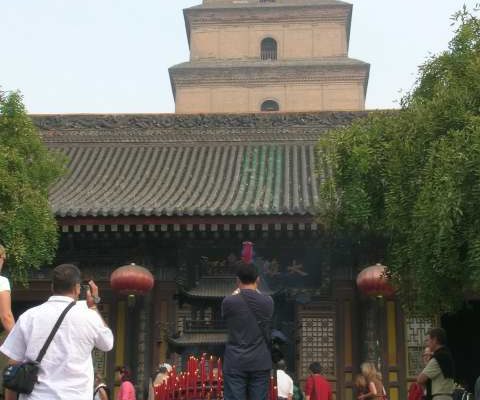

With prof. Sulejman Redžić in Blagaj, a dervish monastery near Mostar

Conference attendees – mainly researchers on medicinal plants in Balkan and Middle Eastern countries and Turkey

Tunnel connecting Sarajevo with the world during the siege

Prof. Redžić talks about crossing the tunnel

1 Comment

I worked with Sulejman in the late 1990s, during post-war efforts to rebuild the local economy, through the US AID Business Finance Office. The war was over, and together we had the chance to see parts of the country that he had not visited for many years. We had many fascinating adventures.

I was so sad to hear about his unfortunate death. If you have contact information for those who may be in contact with his family, I’d love to hear from you.